|

| The Holy Book |

Games Workshop released Inquisitor in 2001 and it blew my nerdy teenage mind. I engaged with it like I never had any game before, and it has fundamentally defined me as a hobbyist going forwards. Everything I do in the hobby now is rooted in Inquisitor. But as games go it was, objectively, quite bad.

The Scale

Titans? They're just like anything else. The bigger they are, the harder they fall.

|

| 54mm be real big, yo. |

The thing that most obviously makes Inquisitor stand out amongst GW’s games is the scale. Uniquely the models were in 54mm, pretty much double the scale of most other games. GW has gone smaller plenty of times, with Epic, Man’O’War, Battlefleet Gothic and more recently Aeronautica Imperialis, but this is the only game where they went bigger instead. This of course meant we had no suitable scenery to play on. We improvised as best we could, and built a few bits of scenery that could work in 28mm and 54mm, but mostly I remember playing Inquisitor around stacks of books, Jenga blocks and a Playmobil toy castle.

But it had an unexpected benefit. At that time in my hobby journey I was still largely painting in flat colours. Suddenly at double scale that just didn’t look good enough to me, so I started a new policy that everything must have at least two colours on it, a wash, a drybrush, a highlight… It’s not much, but establishing that as a bare minimum for Inquisitor eventually carried across as a habit into my 28mm models and hugely improved my painting overall. I’m not a master, not even close, but Inquisitor marked the turning point from crap to decent.

|

| This dude would have looked rubbish in flat brown |

The Range

One can verge from the standard form, but one must always retain their humanity, or be lost to the Men of Iron and their ways.

Somewhat related to the above. Like all spinoff GW games, the range was somewhat limited, although it grew over time as they added more models and conversion kits. But unlike games like Necromuna or GorkaMorka where you could dip into 40k for parts, there really was nowhere else to go for parts. The range was not just slim, but many of the models they had were extremely specific, leaving the more generic models to be used over and over again for all kinds of purposes.

|

| Four of a kind |

But boy did this push my converting skills. Nearly every model I made was a composite of multiple models, carefully hacked apart and then carefully pinned back together. And these weren’t plastic or resin models mind you, this was metal all the way. So most models had four or five pins in them to keep wrists attached and heads in place and so forth. Not just the bodies, I was often creating whole new Frankenstein weapons. It did help a lot that back in those days you could order individual parts from Games Workshop. Whilst it might be slightly more expensive than buying a single pre-packaged miniature, you could purchase this set of legs, that pair of arms, and a head from over here. They also made a few generic weapon and hand bundles that helped enormously.

Some 28mm scale bits did get blended in, where they would fit, but largely as detailing. I also did a fair part of scratch building with paper, cardboard, plastic offcuts and sculpting greenstuff. That last part, Charlie leaned far more into than me, and became rather good.

There was however a very small market for 54mm models, the scale wasn’t entirely invented by GW, and I think I purchased nearly every 54mm model I could find that could fit the aesthetic, and in retrospect, some that didn’t.

|

| Someone made an unofficial Ogryn in 54mm, perfect! |

|

| This film ripoff does at least roughly fit the aesthetic of 40k |

|

| Teenage Tom, that’s an anime character; what were you thinking? |

The Rules

The first rule of unarmed combat is: don’t be unarmed.

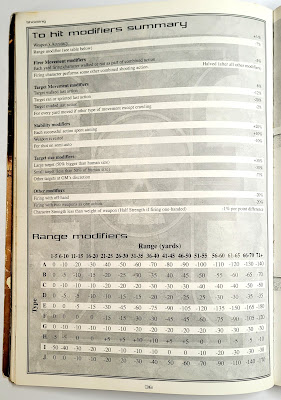

Were far too complicated. For a game that was supposed to be six to ten models on the board, it took an insane amount of time to play and a huge effort to keep track of. At first I absolutely adored the accuracy with which you could replicate action movies down to incredible detail. But after playing it for a while I learned the value in simpler rulesets. My takeaway here is: game design, just because you can doesn’t mean you should. It was a quick hard lesson that hyper-detailed physics simulators might be great in video games but just aren’t fun on the tabletop.

|

| This A4 page is the summary page for how to modify the hit roll. Just the hit roll. |

I also learned about accounting for outliers. The game has fairly complex rules about weapon damage, and armour reducing damage. Without getting bogged down into details, it all works fine for the standard human characters around the baseline, but when you push it out to the Space Marine, who’s stats they have included in the book, an unarmed Space Marine will do more melee damage than a normal human with a Power Fist. If you’ve heard the phrase “the exception proves the rule”, this is what they’re talking about. In this case the exception doesn’t work so the rule is no good.

|

| Brother Punchinator |

The Balance

There is no such thing as innocence - only varying degrees of guilt.

Didn’t exist. Honestly this was something I loved most about Inquisitor. There is no XP spend or points buy or power or anything. The guidance on building your warband was “here are some examples”. A typical warband would be an Inquisitor or equivalent badass with three or four acolytes. But some warbands had Space Marines or Deamonhosts in them, whilst others had a spavined mutant with a gammy leg, no jaw, and bags of enthusiasm. There was no system to min-max, no space for optimising your build, you could do anything you wanted. But, as my late Uncle Ben used to say, with great power comes great responsibility.

|

| Look at all that enthusiasm! |

I learned that the measure of “have I done this right” was “are my friends happy”. There’s no hiding behind “but it’s well within the rules” or “this is a legal build”, it’s just your personal ethics on display for all to see. How much do you care about winning versus a compelling story and your friends’ happiness. As a developing gamer, this was a cold shower for my competitive streak. I think it speaks well for both myself and Charlie that our first warbands were, compared to the warbands presented in the book, somewhat underpowered. I opted for a handful of normal human bounty hunters with no fancy weapons or superpowers at all. Charlie on the other hand, had both super-human Aeldari and a psyker, but tied his other hand behind his back by having just three people in his warband. That said, underpowered though they may have been, they were both weeby as hell in their own ways. Teenage creativity is not known for its discerning nature. Charlie: It really isn't.

|

| Charlie: Naethwir the Eldar Outcast. An incredible sculpt undermined by my baffling basing choices. And also by a real enthusiasm for putting blue and green next to each other. |

|

| Gavin, Yoshi, Barrack and Kimo, freelance bounty hunters. Please don’t judge me. Well, ok, you’re going to anyway, lord knows I do, but please just keep it to yourself. |

The Legacy

In an hour of Darkness a blind man is the best guide. In an age of Insanity look to the madman to show the way.

|

| 28mm of glory! |

Inquisitor was, objectively, awful; but it’s still my favourite game and we are still playing it to this day. In fact on the day I am writing these words we have a game of Inquisitor this evening. But like the Ship of Theseus (or Trigger’s Broom if you prefer) we have replaced every part of it. The rules have been completely replaced by a homebrew system based on Ministry, we no longer play it as PvP warband on warband but as a GMed RPG and when we use models, which is not all that often, we use 28mm to give us a huge range of options and compatibility. But at its heart it’s a continuation of the game we fell in love with 22 years ago, and several key characters that are still around started out life in the original 54mm game.

|

| Oh, wait, I tell a lie. We still use the Hallucinogen table from the original book. |

Inquisitor helped me find out what I loved most about gaming, and then I did more of that. Extensively. Excessively. For decades. We’ve created a huge wiki to document our adventures, map out our setting and generally waffle nerdily. Jeff started us out with the Cetus sub-sector but we now play across two entire sectors. It had a huge impact on how I play 40k as well. When Crusade came along, for many of us it became an extension to that same game, the war-torn sector next door with several characters appearing in both game systems.

|

| The full scale of our hubris |

There’s no good way to end this article, because for us, Inquisitor hasn’t stopped. We’re still carrying on with it, and hopefully will continue to do so for decades more.

Only in death does duty end.

Comments

Post a Comment